After graduating in 1931, he was taken by his father to Tokyo to apply for admission to the newly opened Kobukan dojo. Shirata Sensei perfectly remembers the meeting with Morihei: “Although he was decidedly low, a formidable energy was released from his barrel chest and his thick abdominal muscles. He smiled and laughed continuously, but his gaze remained proud and penetrating. They were two pupils of my age (nineteen years old) were present and the Founder told me to try and land one.

Despite my size and my knowledge of judo, there was nothing to do. She kept hitting me on the mat with a technique, painful for me, that I learned later to be called shiho-nage. That girl was called Kumikoshi Takako and in the future she had some success as an artist. After this humiliating experience, I asked the Founder to become his pupil “. Shirata continues: “It was very difficult to be admitted at that time. It took two trusted guarantors and anyone who did not meet the necessary requirements was immediately rejected. As a result, there were only a few uchideshi. There was no systematic teaching course. When asked about the tuition fees, the Founder used to thunder: “ I don’t teach for money! ”.

Once accepted, a cash offer was placed on the altar of the dojo, and then each student and his family they contributed according to their possibilities. In my case, my father supplied the master with rice and textile fibers. Even after admission I was not allowed to join the training for a few months; I could only watch and take care of the cleaning and other chores of the kind “. After the novitiate period the student acted as uke to the elderly, which meant being scrambled and that’s it. Often at least six months had to pass before the newcomer was allowed to experiment with any technique.

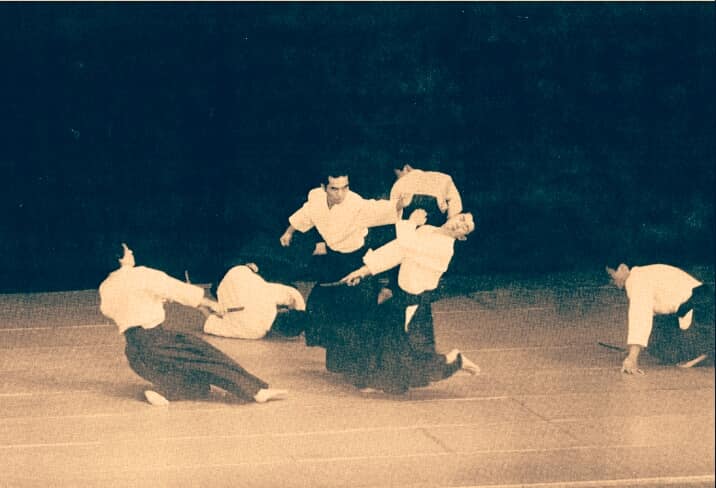

As the country was preparing for a future of military adventures, the training was very tough. To the three daily shifts were added many external trainings and special courses. Furthermore, since at that time the Founder’s system (variously known as Daitoryu, Aiki-jutsu, Aikí-budo, Kobukanjudo, Ueshiba-ryu jujutsu etc.) was considered an art rather than a “way”, it was privileged above all the practical aspect; in the post-war years the Founder’s movements became much more fluid. The Kobukan really deserved its nickname “Dojo of Hell”.

Source: Facebook/Aikido