Until the end of the Edo period, the tailoring of both gofuku and futomono fabrics was separated, with silk kimono handled at shops known as ‘gofuku dana’, and kimono of other fibres sold at shops known as ‘futomono dana’. Stores that handled all types of fabric were known as ‘gofuku futomono dana’, though after the Meiji period, stores only retailing futomono kimono became less profitable in the face of cheaper everyday Western clothing, and eventually went out of business, leaving only gofuku stores to sell kimono – leading to kimono shops becoming known only as gofukuya today.

Historically, all fabric bolts woven for kimono were hand-woven, and despite the introduction of machine weaving in the 19th century, a number of well-known kimono fabrics are still produced in this way. Oshima tsumugi is a variety of slub-woven silk produced in Amami Ōshima, known for being highly desirable as a fabric for casual kimono. Bashōfu, a variety of Japanese fibre banana fabric, is also highly desirable as a casual fabric, but produces extremely few bolts of fabric per year due to the growing methods used to produce the plant. The production of these fabrics has experienced a significant downturn in both desirability and craftsmen over time; though in previous decades, up to 20,000 craftspeople were involved in the production of oshima tsumugi, in the present day, just 500 craftspeople are left.

Other varieties of kimono fabric, previously produced out of necessity by the lower and working classes, are produced by hobbyists and craftspeople for their rustic appeal, rather than the necessity of having to make one’s own clothes. Saki-ori, a variety of rag-woven fabric historically used to create obi from scraps, were historically produced from old kimono cut into strips roughly 1 centimetre (0.39 in), with one obi requiring roughly three old kimono to make. These obi were entirely one-sided, and often featured ikat-dyed designs of stripes, checks and arrows, commonly using indigo dyestuff.

Most ikat-woven, indigo-dyed cotton fabrics – known as kasuri – were historically hand-woven, also due to their nature of being produced by the working classes, who through necessity spun and wove their own clothing before the introduction of widely available and cheaper ready-to-wear clothing.

Indigo, being the cheapest and easiest-to-grow dyestuff available to many, used due to its specific dye qualities; a weak indigo dyebath could be used several times over to build up a hard-wearing colour, whereas other dyestuffs would be unusable after one round of dyeing. Working-class families commonly produced books of hand-woven fabric samples known as shima-cho – literally, “stripe book”, as many fabrics were woven with stripes – which would then be used as a dowry for young women and as a reference for future weaving. With the introduced of ready-to-wear clothing, the necessity of weaving one’s own clothes died out, leading to many of these books becoming heirlooms instead of working reference guides.

Outside of being re-woven into new fabrics, old kimono have historically been recycled in a variety of ways, depending on the type of kimono and its original use.

Formal kimono, made of expensive and thin silk fabrics, would have been re-sewn into children’s kimono when they became unusable for adults, as they were typically unsuitable for practical clothing; kimono were shortened, with the okumi taken off and the collar re-sewn to create haori, or were simply cut at the waist to create a side-tying jacket.

After marriage or a certain age, young women would shorten the sleeves of their kimono; the excess fabric would be used as a furoshiki (wrapping cloth), could be used to lengthen the kimono at the waist, or could be used to create a patchwork undergarment known as a dounuki. Kimono that were in better condition could be re-used as an under-kimono, or to create a false underlayer known as a hiyoku.

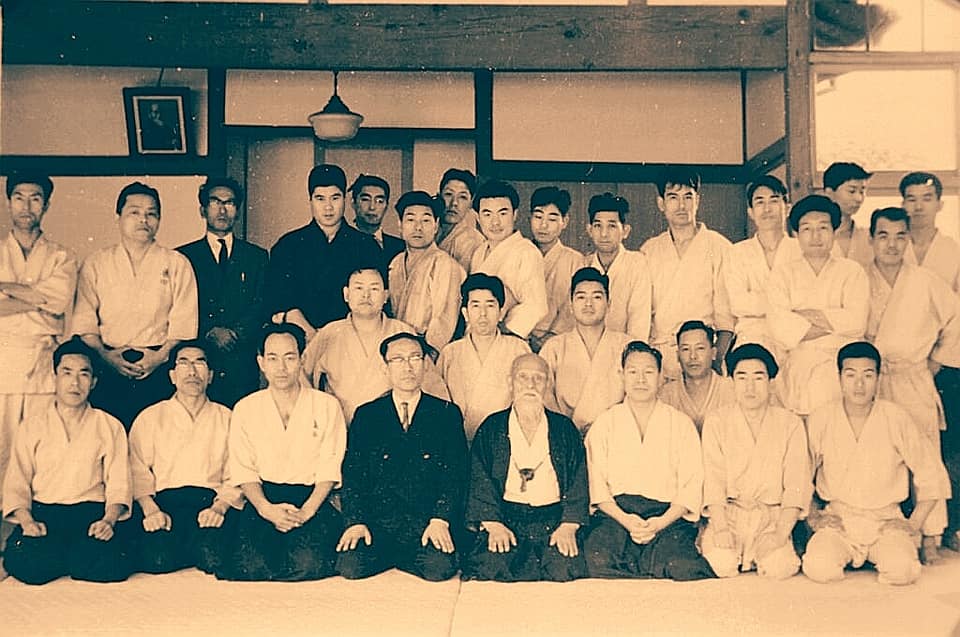

Source: Facebook/aikido